All over the world, public passenger transportation systems in cities represent complicated sectors and traditionally experience recurring conflict due to the complexities that surround it. For this reason, Jorje H. Zalles —professor emeritus at Quito’s Universidad San Francisco, expert in conflict resolution worked with the C40 Cities Finance Facility in unpacking the complexity of Quito’s public transportation system, leading a process for negotiation, consensus building and conflict resolution as a third-party mediator. This article summarises Zalles’ findings and provides some direction towards conflict resolution within the urban transportation sector, which we believe can help other cities learn from Quito’s experience and deal with the conflicts within their own transportation sector.

Aquí puedes encontrar la versión en español del blog. You can also find this blog on the CFF website

All over the world, public passenger transportation systems in cities represent complicated sectors and traditionally experience recurring conflict due to the complexities that surround it.

For this reason, Jorje H. Zalles —professor emeritus at Quito’s Universidad San Francisco, expert in conflict resolution and author of the book 'Theory of Conflict'— worked with the C40 Cities Finance Facility in unpacking the complexity of Quito’s public transportation system, leading a process for negotiation, consensus biuldingand conflict resolution as a third-party mediator.

This article summarises Zalles’ findings and provides some direction towards conflict resolution within the urban transportation sector, which we believe can help other cities learn from Quito’s experience and deal with the conflicts within their own transportation sector.

With possible exceptions, all urban public passenger transportation systems comprise three main groups of actors: users, operators, and transport authorities. Regardless of the ownership of infrastructure and operational structure, it is always difficult to reconcile the desire to deliver both a low cost and high-quality service among these main actors.

According to Zalles’, the conflictive nature of this system has two main causes:

- The desire for a reasonable and sustainable balance among the typically opposing economic aspirations of the main actors.

- The definition of and desire for a reasonable level of service.

The citizens, as users of the system, typically aspire to low fares for public transportation, and, if they need to use two or more system components (metro, buses, etc.) some economic benefit in the form of single or unified fare.

The operators —whether public, private, or mixed— aspire to obtain remuneration of their services that will allow them to at least cover their initial investment in fixed assets (CAPEX) and their operating expenses (OPEX).

Lastly, municipal authorities typically aspire to have a system that requires the lowest possible expenditure of public funds. However, while this would appear to be easily satisfied by the complete delegation of public transportation to private investors and operators, such an approach is essentially not feasible for several reasons, including:

- The demand of many citizens that public transportation should be provided as a right of the citizens and a public obligation.

- The expectation that the authorities should intervene in regulating the prices of essential goods and services.

- The expectation of concessionary fares or benefits for certain groups (senior citizens, the disabled, students, pregnant women, etc.).

Further, both the transport authorities and citizens want a high quality service, which includes:

- Comprehensive coverage that leaves no part of a city without public transportation

- High and sufficient frequency of service even in low-volume hours of the day or night,

- Easily accessible information regarding routes and frequencies

- Compliance with published timetables

- Low crowding in stations and on transportation units even during peak hours

- Comfortable seating

- Security in the face of various dangers

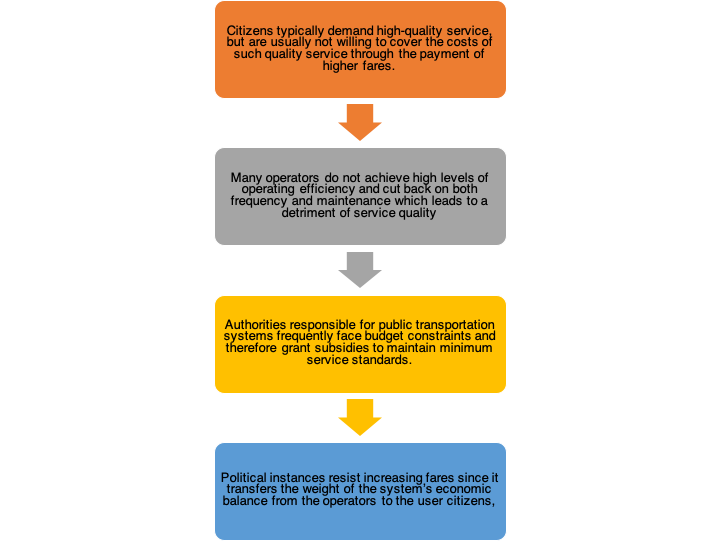

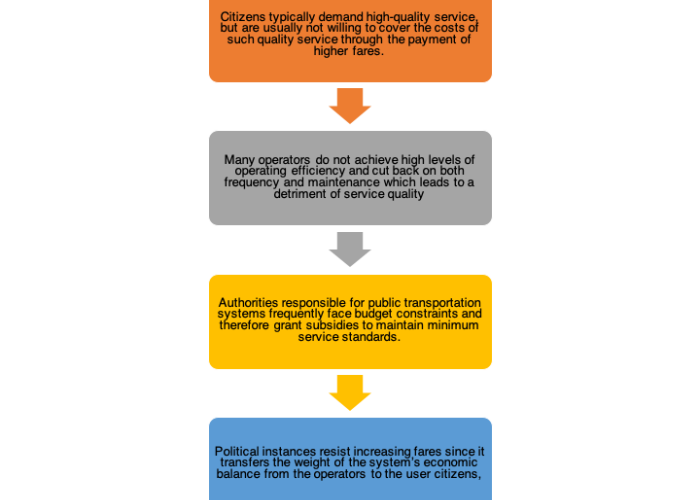

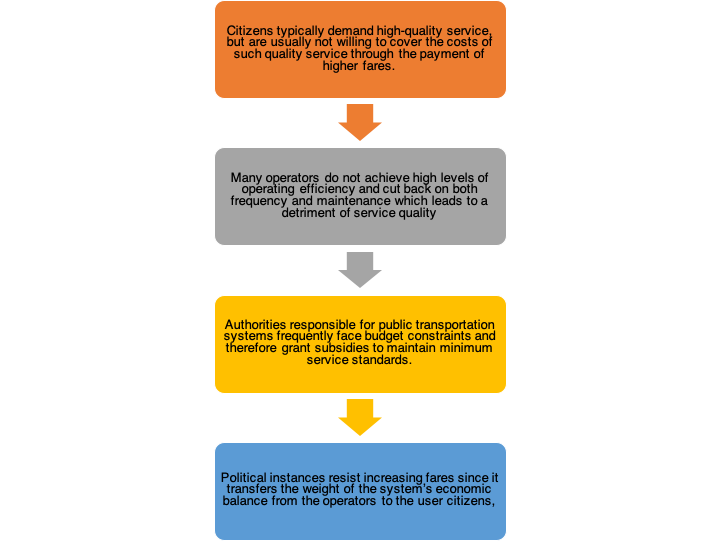

Now, there’s a trade-off between economic and service aspirations and the establishment of a reasonable and sustainable balance between these aspirations is difficult. The following diagram describes a typical situation that may arise as a result of these conflicting aspirations:

This adversarial management of conflicts that are unfortunately common in public passenger transportation systems become even more challenging to manage when a change to the system occurs, such as when considering fleet electrification.

The city of Quito has committed to transition to a zero-emission bus fleet, initially with the electrification of the Ecovía BRT line and the extension of the Trolley-bus from El Labrador to Carapungo. Thus, to facilitate this transition, an impartial third party (Zalles) was hired to establish a system for dialogue and consensus-building, which in turn would create a mutually satisfactory resolution to the conflicts found in Quito’s public transportation system.

The Case of Quito

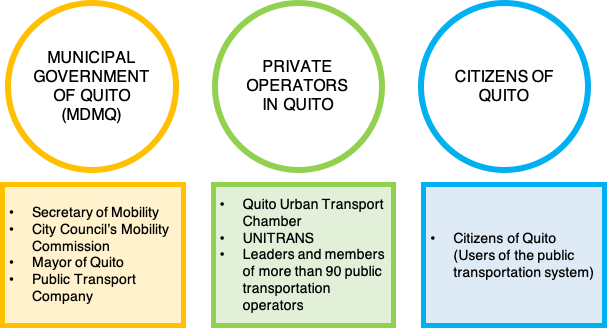

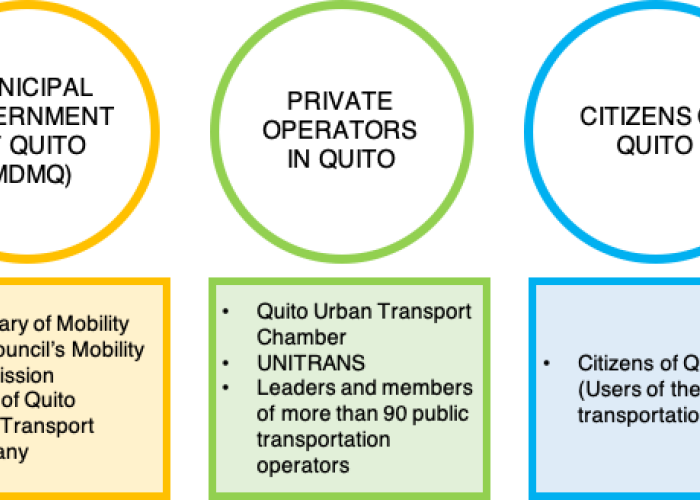

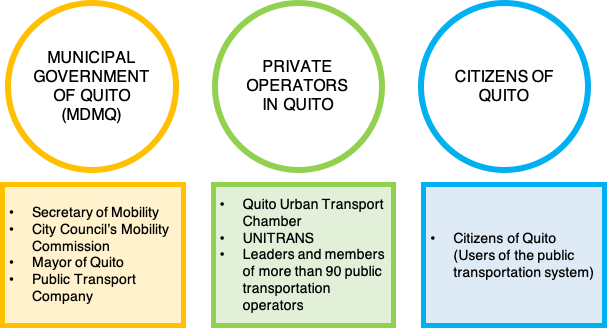

As previously mentioned, all urban public passenger transportation systems comprise three main groups of actors: user citizens, operators, and authorities.

Who are the main actors in Quito’s transportation system?

In general terms, relations between these main actors had historically been confrontational, with limited dialogue and a clear lack of consensus-building strategies. Nevertheless, prior to the mediation process, the relationship between the Secretary of Mobility and the private operators had taken a positive turn and a willingness there to start conversations.

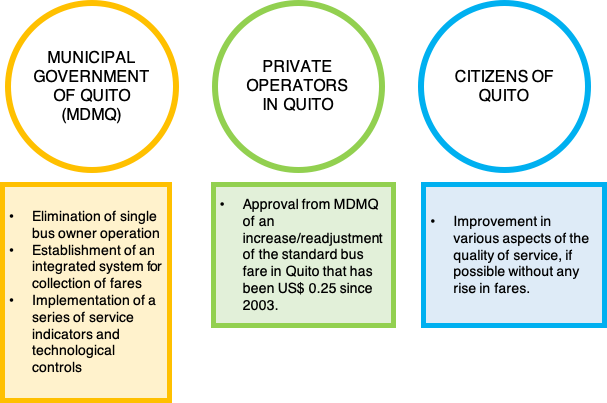

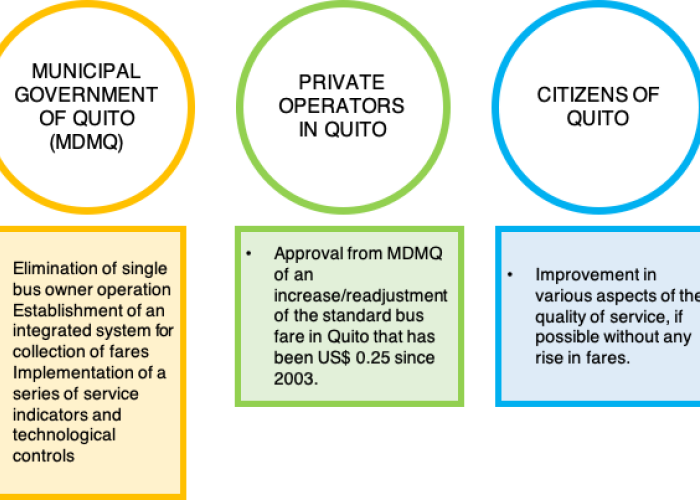

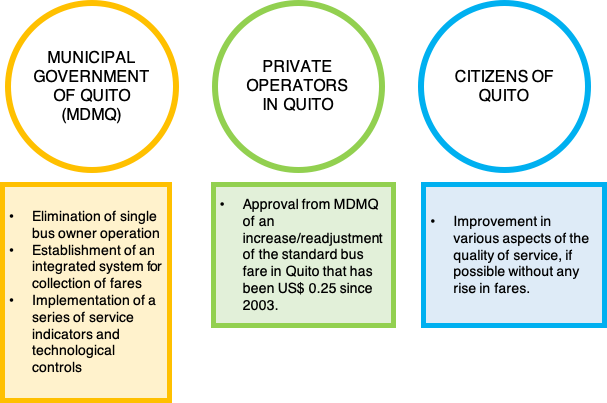

Despite the improvement in communication among these principal actors, they were not systematic in nature, aiming to identify the essential points of conflict and attempting to build consensus-based resolutions. To resolve the conflict, it is important to understand the objectives of each of the parties:

The role of the impartial mediator was to facilitate this communication through:

- Mediating between the Secretary of Mobility and the private operators (as one unified group)

- Mediating among different private operators.

- Providing advice to the parties in order to analyse and identify possible ways to resolve their conflicts and improve communication.

The intervention was carried out as a ongoing process involving meetings, continuous conversations with relevant actors and a systematic documentation of conversations with explicit action points. The generated information was constantly shared with all actors in order to maintain transparency.

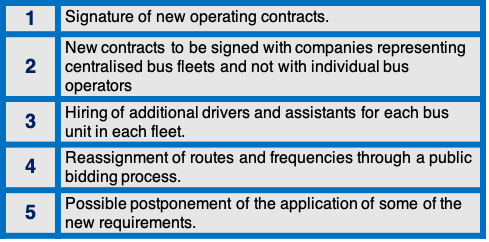

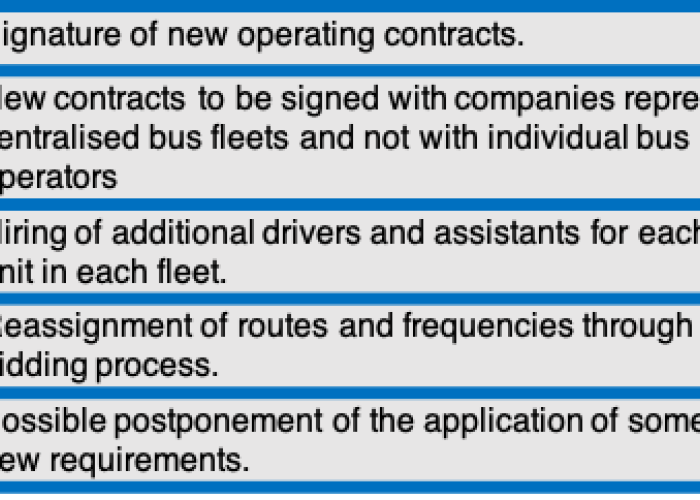

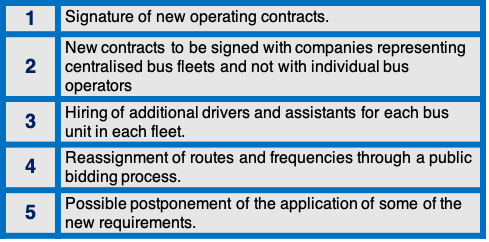

With regards to the topics that were subject to negotiation, there were five main conditions that the Secretary of Mobility established in order to approve the fare increase:

After several months of negotiations in the sessions mentioned above, on November 27, 2020, the Municipal Council approved the new Ordinance which approved the fare increase.

As a direct consequence of the advances that had been made in the negotiations , the private operators had expressed their unanimous support for approval of the Ordinance, and the parties remain in constant contact, working jointly on the Addendum that will ideally contain agreements on the points not yet agreed.

How can cities apply this technique in their own consensus building processes?

A good system of impartial third-party intervention requires the following essential elements:

- A duly trained, impartial and independent third party that assumes the responsibility of convoking, organising and facilitating the negotiation process.

- Open, transparent an inclusive interventions by representatives of the main groups of actors involved in and/or affected by the system.

- A clear and explicit conceptual framework on consensus building that the impartial third party will apply in a consistent manner.

Nevertheless, Zalles states that three conditions must be present in order to consider the existence of “favourable conditions” to carry out this process:

- The simple habit of good dialogue:

Different societies display greater propensity to dialogue, non-aggressive exchange of differing points of view, acceptance of divergent views, and respect for beliefs or preferences of minorities,

- Independence from authority:

In addition, different societies also display a greater or lesser propensity to depend on their authority figures and institutions for taking social decisions and resolving social problems. The existence of “social capital”, represented by a vigorous civil society comprise of multiple organisations and institutions, makes societies better able to solve social problems and face common challenges.

- Availability of competent impartial third parties:

Lastly, there are significant differences among various societies in the availability of educational institutions, foundations, centers, and even individuals able to provide the specialised services of an impartial and independent third party. Where such institutions and/or individuals are available, the consensus building process becomes more feasible and easier to undertake.

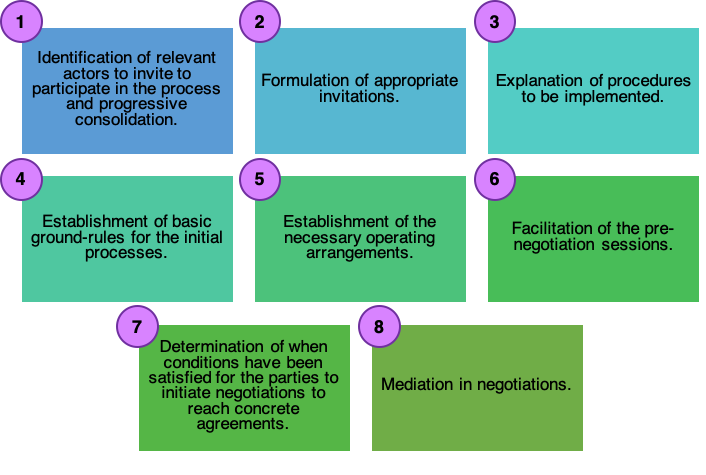

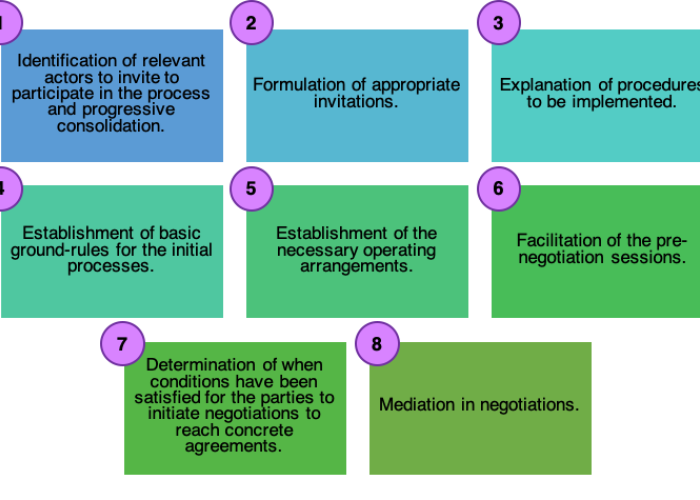

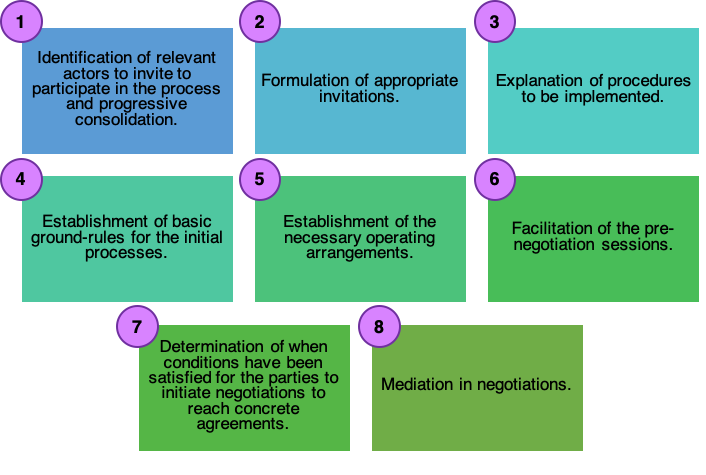

In favourable conditions, the third party would at minimum carry out the following high-priority activities:

However, it could be the case for some cities that less favourable conditions exist due not only to the absence of an appropriate third party in the locality, but also the limited presence of the habit of good dialogue and/or low levels of authority-dependence.

In these conditions, in addition to seeking an appropriate third party outside of the community, the interested parties need to build a citizen coalition, facing five difficult challenges:

1. Recognise the existence of these deficiencies in the dominant paradigms and common habits of the city’s population.

2. Develop social communication strategies that can adequately transmit:

- the existence and negative consequences of said deficiencies.

- the required changes in beliefs, values and attitudes that the situation calls for.

- incentives for undertaking those changes.

- recommendations for undertaking them.

3. Look for advisors to support the development of the social communication strategies

4. Obtain the required funding.

5. Structure an agile and effective organisation for the sustained and persistent execution of the strategies devised.

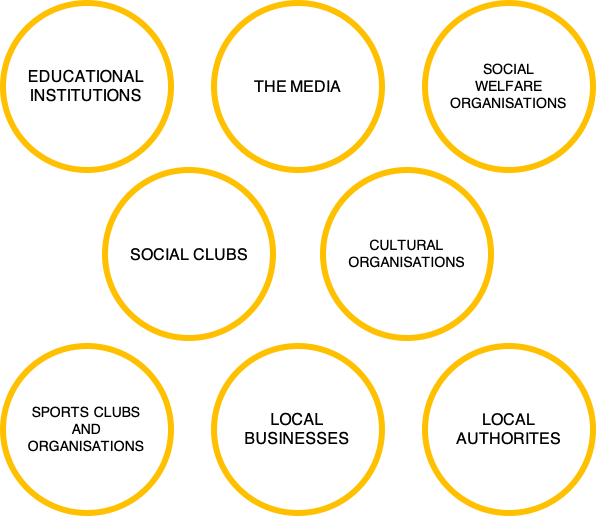

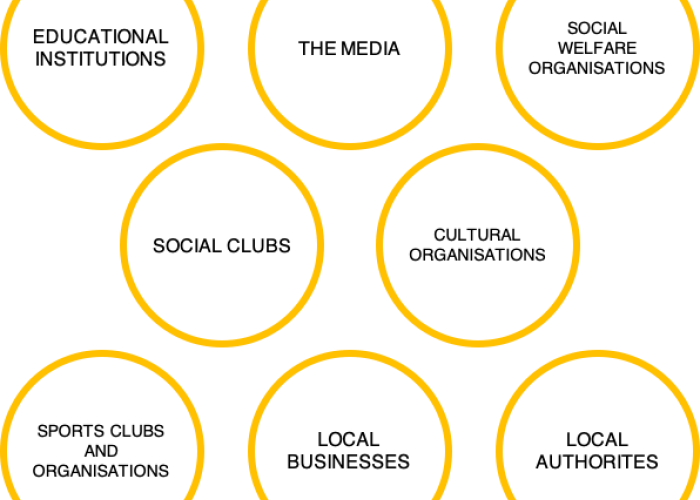

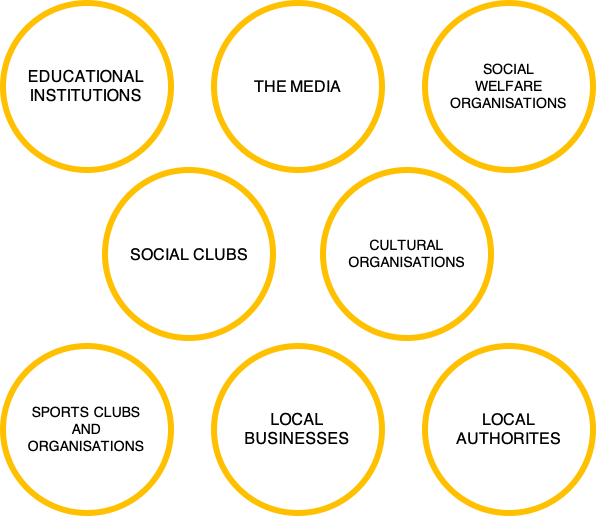

The citizen coalition must include representatives of:

It is worth noting that this type of effort is, by definition, a long-term proposition and results can only be expected after many years.

While many cities don’t consider mediation strategies when conflict arises in public policy scenarios, the presence of an appropriately trained impartial third party can be very valuable to help establish a system to adequately manage conflict within urban public passenger transportation sectors.

You can find this report and further Zero Emission Bus resources from the C40 Cities Finance Facility (CFF) here.